The breeding population of western meadowlarks has been declining throughout the U.S. and Canada at about 1 percent per year since at least 1966

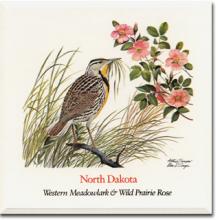

The western meadowlark (Sturnella neglecta) holds a special, almost magical, place in the hearts and souls of those inhabiting the prairies of North Dakota. While it is the state bird, the meadowlark is iconic in its stature because it’s one of the first true tests that winter has relinquished its icy grip on the plains. But across the U.S. — North Dakota is no exception — meadowlark numbers are in a state of decline. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the breeding population of western meadowlarks has been declining throughout the U.S. and Canada at about 1 percent per year since at least 1966.