Why the world’s vultures are vanishing

- Lees meer over Why the world’s vultures are vanishing

- Login om te reageren

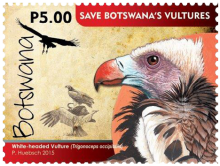

AFRICA is losing its vultures. Of its 11 species of the bird, 6 are at risk of extinction and 4 are critically endangered, according to a recent report by BirdLife International, a nature conservation partnership. Since the 1990s, the population of South Asia’s vulture species has collapsed by more than 99%. In 2003 scientists identified diclofenac, an anti-inflammatory drug used to treat livestock, as the main cause for this decline. Vultures living on the carcasses of animals recently treated with the drug died from severe kidney failure within weeks of ingesting it. This created two main problems. The first is connected to vultures' place in the ecosystem. As their numbers declined, a host of other disease-ridden animals—in particular rabied dogs—came to feed off the carcasses instead. And there was another problem. India's community of Parsees, who not cremate nor bury their dead, but rather lay them out on towers known as dokhmas for vultures to eat, found that this traditional was imperilled. In 2006 the governments of India, Pakistan and Nepal introduced a ban on the manufacture of the drug that has since seen vulture numbers in the region stabilise, though they remain vulnerable.